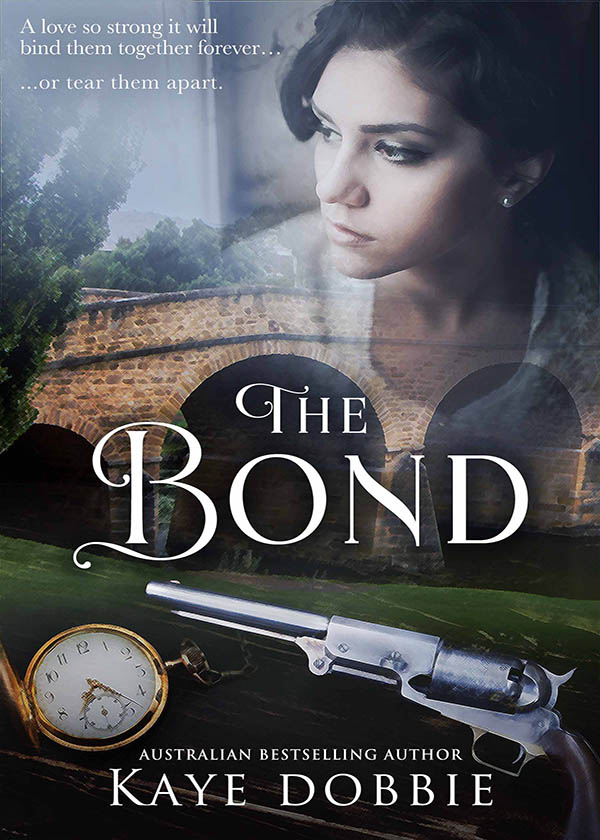

- It begins with a wish made on Midsummer’s Eve, Richmond Bridge, Van Diemen’s Land.

Orphaned Rachel, daughter of a bushranger, doesn’t know that the man she falls in love with isn’t the hero she believes him to be. After they marry, their happiness is torn asunder when Will’s terrible secret is revealed.

With Will gone, Rachel travels to the Port Phillip District to make a life there. As the years pass, their lives separate and intersect, but always there is the bond. Like an unbreakable thread, it stretches between them, holding the promise of a happiness that seems just out of reach. In her loneliness, Rachel turns to another man, while Will returns to his origins, hunting down criminals and bringing them to justice.

Eventually fate brings them together again. Rachel, once more by Will’s side, longs to regain the love she once lost. But Will may never be able to put aside his hurt and forgive her, no matter how much he wants to. Can they resolve their differences at last? Can the wish Rachel made on that long ago evening finally weave its magic?

Excerpt of The Bond

PROLOGUE

Midsummer Eve, Richmond Bridge,

Van Diemen’s Land

RACHEL WRAPPED HER ARMS ABOUT

her narrow body, huddling herself against

the chill. The fury of the mid-summer storm had

lessened, the wind abating and the wild, whipping

rain easing to soft drizzle. The branches above her

head were dripping water down onto her hair.

She shook her head and pushed the leaves aside,

breathing in the cool, fresh smell of the earth.

Before her, through the long grass and reeds,

she could see the swirl of the river, swollen now

with the rain. Ducks were venturing out from

their hiding places for a last foray before nightfall.

A moment ago, she had watched with interest

as a man with a cart came down and watered his

horses, before heading on across the bridge. But he

hadn’t seen her, hidden as she was by the grass and

the low scrubby bushes at the river’s edge.

Behind her, Rachel could see the tangle of dark

smoke rising from the chimneys of the buildings

that made up the township of Richmond. The

orphanage was there among them and Rachel

turned her eyes determinedly away. The sun was

dropping lower, and its fading gleam struck a rainbow

on the shifting storm clouds. For a moment

she let her eyes rest on the mingling colours, wondering

if it were true what they said.

About rainbows and pots of gold.

She could do with a pot of gold. It would solve

all her problems. She hugged herself again, resting

her chin on her bony knees and closing her eyes.

Since Pa had gone—she still did not like to think

of him as dead—there had been no-one to care

about her future but herself. Once Pa had made

plans and decisions, once Rachel had no thoughts

in her head but the sunshine and the flowers and

the warmth of Pa’s coat as she lay sleeping, rocked

by the trot of his horse. But now Pa was gone, life

had taken a different, grimmer turn. These days

all she could think of was her narrow bed at the

orphanage and her tasteless meals and the other

girls with their eyes too big in their little faces.

It wasn’t fair, she thought, and blinked savagely at

tears. Why had Pa had to die? When he was all she

had? He had been a good man. Mrs Roadknight

said so, and Mrs Roadknight knew all her ‘boys’.

She fed them and dried their coats, wet from the

rain, and told the police she hadn’t seen any of

them in months with such a solemn, honest look

in her eye they couldn’t help but believe her, even

when they knew she was lying.

‘He never stole from the poor man.’ Mrs Roadknight

told Rachel. ‘Only the rich, and then he

were so courteous, they had no complaints. That’s

why it took so long to catch him, you see. No

one wanted him caught. But the reward . . .’ and

she shook her head, ‘ten pound is a lot of money,

Rachel. And some men being what they are . . .

One of them bounty hunters it was, finally tracked

him down.’

So Pa’s gallant career on the road had come to an

end. He had been shot while resisting arrest, and

so there was one less bandit to swoop down on the

little settlements and the lonely travellers, one less

bandit to annoy the authorities of Van Diemen’s

Land. Not that there weren’t plenty of others to

take his place! But Pa had been special. Even Mrs

Roadknight, who ran the End of the World Inn on

the road between Pitt Water and Jerusalem, and to

whom they were all special, thought he was a cut

above the rest. The inn was a notorious bushrangers’

stopping point, although the police could

prove nothing and were usually so undermanned

they did not even try.

When Pa had been killed, Mrs Roadknight had

taken Rachel in. The little girl was only five, and

for the next three years she remained there, slightly

neglected, but loved well enough and treated like

a little princess by all the ‘strangers’ who called on

Mrs Roadknight at odd times of the day and night.

Rachel learned from an early age to view the law

with suspicion, and believe wholeheartedly in the

myth of the bushranger—the gallant man ill-used

and ill-treated by a cruel society, who was compelled

to escape into the bush and live by pillage

and theft, evading the police as best he could.

In some cases it was true enough, but in others

the men who called themselves bandits or

bushrangers were savage and without conscience

of any kind, sometimes even a little deranged by

the cruelty they had endured in the convict camps

and roadgangs. Not that the child Rachel comprehended

such things. She just knew that there

were some men whose eyes frightened her, and she

stayed away from them.

The police finally decided they’d had enough of

Mrs Roadknight and closed down the inn on the

Jerusalem road. And Rachel, eight then, had gone

to the new orphanage in the growing township of

Richmond. She was no longer treated like a little

princess; she was just one of many little girls who

had been abandoned.

Rachel swallowed, lifting her head again. Her hair

had come loose as always and was wild down her

back. A thick, black cloud. The rain shone in it, like

droplets of silver. She loved the weight of it, pulling

at her neck. There was a rule at the Orphanage that

hair should be kept up under a bonnet at all times.

But there was no-one here to see.

‘Gypsy black.’ That was what Pa had called her

hair. It shone in candlelight with a blue sheen. Her

face was pale and would one day be a perfect oval,

but now it was too thin, too angular for beauty.

Her nose was straight, perhaps a little long, and her

eyes were dark and secret, slanting at the corners,

as black as her hair.

‘There’s Spanish blood in us,’ Pa used to tell

her. ‘One of our ancestors was wrecked from

the Armada, in Drake’s time, and found his way

to Devon.’ It sounded more romantic than being

called ‘gippo’ or ‘black’ as they travelled about Van

Diemen’s Land. For, when he wasn’t being a gallant

highwayman, Pa was a hawker … a tinker, selling

to the lonely wives and women of the settlements

throughout the island. Pa had a way with women.

Even then Rachel knew it. And knew some of

them came willing to his bed. But it was never

more than that. It was Rachel who was his companion,

his friend, his apprentice.

The light was fading fast. She would be missed

soon at the orphanage. She had her duties to perform—

helping with the cooking and the cleaning,

helping the smaller ones. Because Rachel was thirteen.

It was eight years since Pa had died, although

at night when she closed her eyes she could still

feel him close. The tears stung again. Usually she

held them back, but because she was alone in the

twilight, this time Rachel let them come.

She wept for a long time. It was so unfair! Pa

had been all she had and, although life had been

sometimes hard and uncertain, at least she had had

someone. It was the sense of belonging she missed

more than anything. The orphanage was so cold.

They were fed and clothed and generally looked

after, physically as well as spiritually—on Sundays

they made a long crocodile and walked to church

for their worship—but emotionally . . . she felt as

empty and desolate as the great craggy mountains

to the west. And for someone like Rachel, so warm

and eager to love, so desperate for love in return, it

was sometimes so unbearable she just had to escape.

Like now.

Just to be alone with her memories and her

thoughts, to regather her inner strength. To remind

herself who she was, a person in her own right,

rather than just another nameless body in an

orphanage uniform . . .

Suddenly behind her, a twig crunched. Rachel

glanced swiftly and nervously over her shoulder.

At first, she could see nothing. The darkness had

grown thicker in the moments she had been grieving

for the past. And then a shape moved, a figure

on a horse. The animal wickered softly, nuzzling

the long grass, and Rachel’s heart began to beat

with frightened thuds. It was dangerous out here

alone. There were ruffians; thieves and murderers

not so gallant as her father. Rachel crouched, ready

to run.

‘It’s all right,’ a voice said, soft and low with a

drawl she found familiar, a little like Pa’s. ‘I came

to water the horse and I heard someone cryin’. Are

you hurt?’

Rachel watched, wide-eyed, as the man urged the

horse closer. He was a dark shadow in the evening

shadows. She could not distinguish his features at

first, and it was only when he dismounted that she

saw him better, but still not well enough to colour

the hair flopping over his eyes. His shoulders were

broad from hard physical work, and his mouth and

jaw had a straight, stubborn look at odds with the

concern in his voice.

‘Are you hurt?’

She shook her head, and wiped her face with

her sleeve, scrubbing at it roughly, as if to eliminate

all traces of her weakness. ‘I was just thinking sad

thoughts,’ she told him warily.

He looked at her again, and the hard mouth softened

into a flicker of a smile. ‘What sad thoughts

would they be, darlin’?’

‘I was thinking of my Pa.’ She looked at him again,

slyly out of the slanting eyes, to see what effect that

was having. ‘He’s dead and I’m an orphan.’ Comprehension

came into his face. ‘You’re from the

orphanage,’ he said. ‘Should you be out here by

yourself?’

Rachel shrugged indifferently, but fear wormed

its way into her mind again, and she glanced rather

nervously towards the smoke from the town, now

a grey smudge in the dark sky. She would get into

trouble. There would be no supper for her tonight,

and probably she would be birched if Mrs Hewett,

who was in charge of them all, was angry enough

with her. And yet, she rarely got to speak to a man.

The orphanage was for girls only, run by females.

She missed the male attention she had had at Mrs

Roadknight’s inn, and she missed her Pa. This man

sounded rather like her Pa. She could not bear to

leave him just yet.

He was standing so quietly, as if lost in his own

thoughts. She looked at him curiously. ‘Are you

from the town? Have I seen you at church?’

He smiled. ‘Well, I don’t go all that often. Have

you always lived here?’ he added, shifting the subject.

‘We travelled all over, Pa and I,’ she murmured

softly. ‘He was a friend of Matthew Brady, or so

Mrs Roadknight said.’

She felt the man stiffen. ‘You mean the bushranger,

Brady?’

‘Yes.’ she sighed. ‘And my Pa was a gentleman,

too. He didn’t hurt anyone. He only took what he

had to, and he was always polite and always kind to

the ladies. But they caught him one day, the police

troopers and their hired killer, and shot him dead,

and so I was left all alone. I stayed with Mrs Roadknight

for a time, up at the End of the World Inn,

but the police closed her down, and she went to

her sister in Hobart Town. There wasn’t room for

me. So I came to the orphanage to live.’

He was silent for so long she wondered what he

was thinking. Usually, when she spoke of Pa and

Mathew Brady, there were cooes and murmurs of

excitement and admiration. But when the stranger

spoke again it was only to say, ‘Have you any other

family you might go to?’ His voice was a murmur

in the darkness, as though, she thought with a pleasurable

shiver, he was part of the darkness itself.

‘Not that I know of,’ she told him cheerfully. ‘Pa

never spoke of any, if I do.’ A breeze stirred the

leaves above her head, and she lifted her face to

its coolness. There were a few, faint stars now. ‘My

mother died when I was only a baby,’ she added,

and tried without success to feel sorrow. She had

never known her mother, and so could not miss

her. ‘Pa said she was already married to someone

else when he met her, and they lay together for

seven nights and then her husband returned and

Pa went away. But when I was born, my mother

died and told her husband the truth before she did.

He found Pa and handed me to him like a bundle

of old rags, so he said.’ And she laughed, for Pa

had made it sound so funny when he told her. ‘So

I have no Ma and no Pa, and that makes me an

orphan. That’s why I was crying.’

‘I can understand that,’ he said. ‘It’s not easy being

alone.’ There was bitterness now in his voice.

Perhaps he was one of the convicts, exiled from

home and loved ones, sent to be punished with

lash and hard labour? Or perhaps he was a settler,

who had travelled halfway around the world looking

for fortune and found only misery?

‘Have you any family?’ Rachel asked gently.

‘Not any more,’ he told her, and it was the sheer

expressionlessness of his voice that touched her

heart. His hand was resting on the branch near her,

and some impulse made her put her own small

palm over it.

‘Then we are two of the same,’ she told him, in

what was meant to be comfort.

He seemed surprised. She felt his hand twitch,

and then relax again under hers. ‘Maybe we are,’ he

said, and amusement warmed his voice.

‘Where are you from?’

He pushed back his fringe, and it flopped immediately

back over his brow. ‘I’ve been working over

Sorell way. I’m on my way home at last,’ and he

laughed with a mockery she couldn’t understand.

But she felt compassion and a sense of companionship

overcome her wariness for a stranger. For

whatever reason this man was alone and unhappy,

and something in him reached out to her as if they

were truly, as she had said, two of a kind.

Rachel looked up at the stars again, and suddenly

her mood lightened. ‘Do you know what night

this is?’ she asked him in a whisper that barely suppressed

the excitement in her voice. As though she

were about to present him with a gift.

He shook his head without answering.

‘It’s my birthday,’ she said. ‘I was born on Midsummer’s

Eve. My Pa used to say that Midsummer’s

Eve was a magic night—you know, old magic. He

said I could make a wish and it would come true.’

‘Have you ever made one?’ he asked her, and she

felt him move closer and squat down beside her.

‘Sometimes,’ she murmured, ‘but they didn’t

come true. Maybe I wished for too much.’

She saw him smile, bending his head, and tossed

her own indignantly. He looked up at the movement

and his eyes gleamed with a moist sheen that

made her wonder if he had tears in them. Was he a

ghost, a lost soul, uncared for and unwanted, come

to haunt the river bank? There was supposed to be

a ghost here, but she had forgot exactly what it was.

Rachel felt her skin prickle.

‘Don’t you believe Midsummer’s Eve is magical?’

she asked him quietly, her voice full of fright.

He took a moment to answer her. ‘My father

used to say I was a Moonraker, so maybe I do.’

Rachel tilted her head to one side, her fears forgotten.

‘What’s a Moonraker, sir?’

He laughed, and it was a warm laugh, the laugh

of a friend. ‘That’s someone who sees the moon’s

reflection in a pool of water and thinking the

moon itself is floating there, tries to fetch it out.’

Rachel sniffed. ‘A fool, you mean! Well, I will

make my wish, whatever you think.’ There was

a silence, while she did—I wish to see this man

again—and then wondered, irritably, why she had

wasted it on such a thing. She should have wished

for something like a pot of gold, or a loving home

and family.

‘What did you wish for?’ he asked her, trying to

make his voice serious.

Rachel bit her lip. She would not tell him the

truth. He would laugh at her. Instead, she spied the

horse, still cropping the grass, and smiled. ‘I wished

you would take me for a ride on your horse,’ she

told him slyly.

He seemed to be considering it, and then he

stood up. ‘Why not?’ he mocked, as if to himself.

‘It’s not often I can make someone’s wish come

true!’

Rachel’s heart leapt. He mounted, and held

out his hand, reaching for hers. Without a second

thought she gave it to him, feeling his fingers close

hard, and then he had pulled her up into the saddle

before him, his strong arms either side of her. She

felt his breath in her hair, and turned her head to

meet his eyes. His hands tightened on the reins,

and the muscles in his arms hardened. ‘Where do

you want to gallop to?’ he asked her evenly. ‘Will

we go to Hobart Town and back, or on and on into

the sea?’

Rachel laughed, hearing the edge of excitement

in his voice, although he strove to hide it, matching

her own. ‘The sea!’ she cried.

He kicked his heels savagely into the horse’s

flanks and set it speeding away, down the road.

The wind was in her face, streaming her hair out

behind her, making her cheeks sting and her eyes

smart. Neither of them spoke. The rain had cooled

the air, and it was delicious and so exhilarating,

she felt as if she were flying. In all her young life

she had never felt like this, riding like the night

wind with this stranger. The excitement twisted in

her, making her laugh out loud, and his arm tightened

about her so that she was pressed hard against

him. The horse stumbled, but somehow he held it

upright, and she felt the power of his body with a

sense of wonder. She felt small and protected, as if

her father was with her again, only different in a

way she couldn’t understand. Rachel pushed her

hair out of her eyes and smiled to herself. I’ll never

forget this moment, she thought. Not as long as I

live. When I’m old, I’ll still hug it to myself, and

remember.

After a while, she realised he had slowed the

horse to a trot. It was puffing and blowing, its sides

heaving. It could not be an easy thing, she thought,

carrying the two of them. In dismay, she saw the

lights of Richmond before them, and knew their

journey had come to an end. He kicked the horse

into a canter again, and its hooves flicked up mud

and grass along the riverbank. Some water birds

flew up, squawking their displeasure at being disturbed

so late, and Rachel turned, laughing, to

meet his eyes.

He paused a moment, hesitating, and then suddenly

he leaned forward. His lips brushed hers in

the darkness, warm and soft. Rachel was so surprised,

she did not move, and felt his smile even

though she could not see it. ‘You’re a lovely girl,’

he told her. ‘I’m glad I could make your wish come

true. Now you’d better be going, or you’ll be in for

trouble.’

Reluctantly, Rachel slid down. ‘Will I see you

again?’ she asked him. ‘Will you come back again?’

He smiled. ‘Maybe I’ll be here next Midsummer’s

Eve to grant you another wish, darlin’!’

She laughed, as he had meant her to. She moved

away, backwards, still watching him darkly silhouetted

on the horse against a sky which was now

full of stars.

‘What’s your name?’ he asked her suddenly.

She had started to run, back the way she had

come. ‘Rachel, it’s Rachel,’ she called, her voice

fading in the darkness. And she ran on, skipping

and laughing, not caring that when she returned

there would be angry faces and she would go to

bed sore and hungry. It was her special secret, and

she hugged it to herself, and thought of it often

and never forgot it. And although she was by the

river the following Midsummer’s Eve, waiting in

the darkness with fast beating heart, he did not

come. And she wondered if he had been a ghost,

after all.